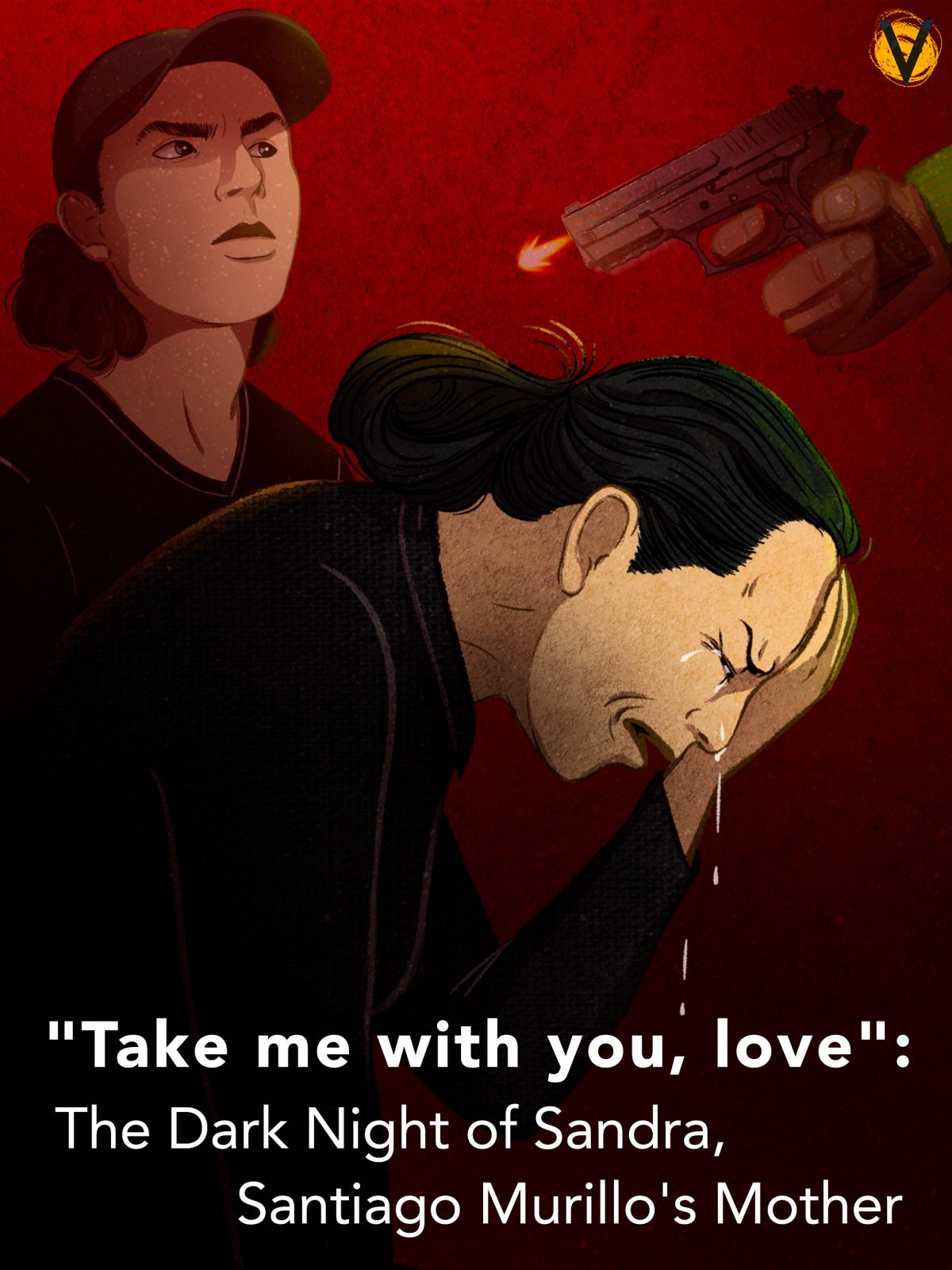

“Take me with you, love”: The Dark Night of Sandra, Santiago Murillo’s Mother

10 de mayo de 2021

Sandra Milena Meneses Mogollón screamed and cried the way you can only scream and cry when a piece of your body is torn away. The scream came out broken and shrill. It sounded in the background like a ragged whimper mixed with crying. It was an unconscious reaction, a burst of air that entered the lungs, passed through the vocal cords, and came out with a force that would have been able to blow up a leaf had there been one in front of her.

In front of the entrance of the Nuestra clinic in Ibagué, at 9:15 on the night of May 1st, Sandra Milena was receiving the news: her teenage son, her only child, the one she had planned with her husband for two long years before becoming pregnant, was, at that moment, leaving this world forever, with a gunshot wound to the chest.

“They killed him today! Then make them kill me because I’m leaving with my son!” she shouted.

“I’m leaving with my son, I’m leaving with my son, he’s my only son!” she screamed.

“Then kill me! They’ll have to kill me! They have to shoot me, too! Where are they!? Where are they!?” she shouted, as if she wanted to be taken to the murderers.

Her lament was heard several meters away, and was caught askance on camera and firmly by the microphone that journalist Miguel Ángel Figueroa, from the radio station Ecos del Combeima, had on. At that moment, he was interviewing Laura Fonseca, from the Human Rights Network of Tolima, who, with a broken voice, was denouncing the excessive actions of the Police’s ESMAD (Mobile Anti-riot Squadron) in the marches that had taken place on Labor Day and against the tax reform that the government of Iván Duque intended to pass in Congress.

Seconds before Sandra Milena’s scream was heard, a 19-year-old girl was crying nearby. She had thick black curly hair; she was petite. The girl was holding a pink backpack on her legs as she was being taken care of by a nurse on the sidewalk:

“Some police officers were kicking me when I was on the ground. I have epilepsy,” she said.

“How long ago were you diagnosed with epilepsy?”

“When I was 11 years old.”

“You have a blunt force trauma and a ten-centimeter hematoma, okay?” the nurse said.

They were having that conversation when, two steps away from them, Sandra Milena let out her first scream of pain. She had just been told that Santiago had not survived a bullet that entered through his thorax and found an exit through his right arm.

“Take me with you, my love! Son! My son! Take me, my love! Son! Baby! Take me with you, my love! My son, take me with you! Please, take me with you!” she cried out of her mind, in shock.

The cameraman, out of instinctive tact, shifted the camera focus away from Sandra Milena and towards the clinic. Only the façade of the hospital was visible. In the images, you could barely see a cold and opaque window with metal bars. And, in the back, very close, but not visible on the screen, the sound of Sandra Milena’s harsh and muffled cry was being recorded. It was the most faithful and accurate scene of what desolation really is.

They say that human beings scream and cry at birth because it is the only way to establish ourselves in the world as someone who exists and who needs others. Sandra Milena had heard her son Santiago Murillo’s first cry in a clinic on December 24, 2002, the day she gave birth to him 19 years ago. But then, screams also appear at other ages as a way of expressing the unimaginable. It is a defense mechanism that indicates that there is something beyond words, something beyond our capacity of understanding. Someone would tell me the next day that Sandra Milena’s scream seemed as heartbreaking as it was unbearable. And maybe they were right. It cannot be endured, since it is against nature for a mother to assimilate that her child has just been killed. Sandra Milena’s screams —the screams of a mother for a child who has just died— could very well come from the womb, that bloody and perfect place where the gestation of the baby, who later cries and screams, begins. And that is why they resonate, that is why they deafen, that is why they rumble, that is why they crush the soul, that is why they are unbearable.

**

At about 8:30 on the night of May 1st, Santiago was on his way home when he bumped into a group of police officers. He was alone, walking northward along Carrera Quinta, one of Ibagué’s main avenues and, if anything, the busiest. Very few cars were circulating. At that time, the city was still experiencing the remnants of chaos caused by the marches that had taken place during the day. The Human Rights Network of Tolima, the department of which Ibagué is the capital, was denouncing at the end of the day that the police had violently repressed the protest, that they had rounded up and gassed the inspectors, and that, as a total estimate that added a mantle of anxiety to the already dark night, 25 people were missing. That is what Laura Fonseca, the spokesperson for the network, said.

On the corner where Santiago had arrived there was only a dim light. The streetlights dripped some yellow spots on the asphalt. A dozen uniformed men were scattered on the end of the sidewalk where the Panamericana bookstore is located, just where Santiago had to cross over to get home. He probably felt trapped on the other side of the street and hesitated several times whether to cross or to stay there for a few minutes. Perhaps the fear of passing through the street divider bit his insides for a few seconds. An ESMAD tank with ballistic protection was advancing slowly towards the south in the against traffic.

Santiago was wearing a black cap, a long-sleeved dark hoodie, one of those Totto backpacks that have a padlock. He had walked from his girlfriend’s house, Estefanía Silva, who lives very close to the Manuel Murillo Toro Stadium. Santiago’s last walk may have taken 29 minutes, a little more, a little less, over 2.4 kilometers. Santiago had made sure to leave his green Trek bike at Estefania’s house to prevent it from being stolen. He had had it for a year and it was a valuable object for him, almost to the point of worship.

Before leaving, he called his dad to pick him up in the taxicab that he drives to take him home. However, the cellphone of Mr. Miguel Murillo, who was driving around the city at that time, working, had a depleted battery. Santiago had no other choice than to head out on foot. Until he reached that corner where his life was to be struck down.

Two blocks away, in a building with a brick façade on 62nd Street, Santiago had lived 19 years of his life. The friends he grew up with always called him Pirry and he did not mind this nickname. He never hung out in groups, he spent his time with his girlfriend, sometimes riding his bike, or walking a puppy named Violeta that he had adopted from a pet shop. Juan Rojas, his cousin, his best friend, his buddy and brother in life told me that Santiago was not a follower of the latest trends. He always wanted to go against the most essential matters of life. While all his friends leaned towards the reggaeton trend, he would rather listen to The Weekend. If the kids on the block wore black, he preferred white T-shirts. And he did not care what people thought of him.

Juan is 17 years old. He was a little nervous when I called him. His voice was quavering and cracking from crying. He told me that on the day of the May 1st protests Santiago was not marching: his presence there had been drawn by chance. But they had gone out on the streets together on Thursday, April 29th. Although his parents had urged him several times not to go out because of the dangers and stories of outrage and violence in the streets, Santiago wanted to be there with Juan to support the strike. They walked, laughed, shouted, talked, and went back home. Santiago was struck by a genuine drive to complain to the Government about something he did not consider fair. His last Facebook post shows that his intentions were never violent. He talked about using paint with the ESMAD, as a “non-offensive” method. “It is not violence because it does no physical harm,” he wrote.

In Ibagué, young people have many reasons to protest. I grew up in that city, which now has around 600,000 residents and is three and a half hours away from Bogotá. In the Jordán Séptima Etapa neighborhood —which, in the landscape, looks like a handful of houses scattered around a hole surrounded by mountains— the thought of someday going to college was always an impossibility. It was like a wall you grew up against and climbing it did not seem like a given right, but a utopia. The alternative was to leave, to find luck elsewhere. According to the latest DANE (National Administrative Department of Statistic) numbers, 236,696 people live in poverty in Ibagué, that is more than a third of its population. Not to mention that during the coronavirus pandemic, extreme poverty increased 300% and now there are 72,675 Ibagué citizens in this cruel measuring range. Ibagué is the fourth city with the highest unemployment rate in Colombia. Although Santiago never lacked anything, it is not as if he lived in abundance. Sandra Milena is an esthetician and makes ends meet with clients she welcomes in her apartment. His father, Miguel, drives a taxicab. Santiago said several times that he wanted to start his own clothing company, he dreamed of having a jacket line. That was the reason Sandra Milena entered the SENA (National Training Service) to study pattern design. It was their plan, it was the next thing after Santiago finished high school.

Sandra Milena tries to capture in her head the last image she has of Santiago in life. She pictures him home, almost ready to leave to his girlfriend’s house:

“Mommy, can I eat the chicken skin?” that was the last thing he asked her. And she, while doing a client’s nails in the living room, told him, looking at him out of the corner of her eye, yes, of course, and that he should be very careful in the street because things were bad, that he should spend the night at Estefanía’s, who was always by his side. They did not get to kiss goodbye. They only got to say goodbye. Mr. Murillo put the bicycle in the trunk of his cab and took his son. They agreed to text each other later.

“Mijo, let me know when to go pick you up,” he said to him for the last time. His cellphone was running out of battery and Miguel had not noticed.

You might also like: “Dígale a mi mami que la amo”: el último suspiro de Julián González, asesinado por la Policía

**

Eyewitnesses are pivotal when investigating a crime. Janer Andrés Galindo did not know Santiago, but he was there. He saw everything. He was a tall, 20-year-old, dark-skinned boy with a piercing in the upper part of his nose, in between his eyebrows. When Santiago was shot, Janer approached the Nuestra clinic. He was holding a black coffee, and was sweaty and worried. His account is very important:

“It’s awful that police officers use their guns against the people, we don’t have the same force potential as they do. I found a girl first, she was by herself, I accompanied her and told her to be with me so that she wouldn’t be alone when something happened. We were walking down 5th Street and found a group of kids on their own, I pulled them along too: ‘Hey guys, you’re alone, let’s go to where the others are.’ When we got to 60th Street, the tank was coming down and a group of police officers on motorcycles arrived and stopped there at the corner of the Panamericana bookstore,” he said.

At that moment, Santiago should have already been at the corner and getting ready to cross the street.

Janer continued:

“We were coming from the opposite lane, going down, empty-handed, making no noise, not looking for a fight, not protesting, and the tank went up again. A guy throws a rock, it makes a sound; when it hits, you can hear the weapon setting off. A kid that was crossing the street screams, he shouts “Help! Guys, my arm!”, scared because [he] didn’t know if he had been shot in the arm or somewhere else. Further ahead, the boy fell. I went straight to the police officer who was there, I objected and asked him why he was using his weapons against us, we had nothing on our hands.” According to Janer and the young woman whose name I will omit, Santiago was shot by a police officer in a motorcycle.

A video published by the website ElOlfato.com shows what was happening minutes prior to Santiago’s arrival at the scene. A group of hooded people had thrown rocks and faced some police officers right at that spot. Both sides threw rocks at each other. “Look, police officers throwing rocks,” says the man who is recording the video on minute 2:23. And then 20 shots were heard. There could have been a lot more bloodshed than there was. Spirits were on the brink of cataclysm.

The decisive part of the video comes afterwards, almost at the end, after the previous riot had been dissipated. The video does not show the moment when Santiago is shot, but the images serve to showcase the elements of the scene, which match Janer’s testimony. The presence of the tank, the rock, and the gunshot is evident —even if they are not shown— when the feminine voice who was with the man recording the video mentions them.

“They shot him! They killed him! They shot him! No! They shot the boy!” says the woman, while the cellphone camera points to the group of young people who came to help Santiago.

“They killed him,” the masculine voice says.

“Call an ambulance!” she says.

Around Santiago you can see the others shouting and asking for help.

“They didn’t even do anything in the end,” says the man recording with his cellphone.

“No! They threw that at the tank, it wasn’t even directed at them!” the feminine voice blurts out.

And that is precisely the phrase that does not disprove Janer. It speaks of how they threw something at the tank and not at the police officers. And Santiago was there, alone, as if imprisoned on the sidewalk, not being able to cross the street. The video ends. What happened afterwards could be summarized in one word: despair. The ambulance comes and takes Santiago away, who at that time still showed signs of life. Some police officers went to the hospital and asked for their victim’s backpack. They broke the lock, searched it, and found nothing. This fact was denounced by Mr. Murillo.

I am finishing this piece of writing four days after they killed Santiago, and we still do not know the name of the police officer who shot him on the chest. The Inspector of this institution, General Luis Ramírez Aragón, traveled to Ibagué on May 2nd and, there, he announced an internal investigation had been put in place. This case is also on the hands of the Colombian Attorney General’s Office and the Colombian Inspector General’s Office. While I write these lines, I am reading that, according to the Colombian Ombudsman’s Office, during the protests that took place between April 28th and May 4th, 10 people may have died at the hands of the Police on the streets. The NGO Temblores, an independent organization, states it is 31 people. There is reason to suspect official figures. The Ombudsman’s Office, the Attorney General’s Office and the Inspector General’s Office are all lead by people akin to the Government, the same Government that the people are protesting, and a process of international verification that can provide certainty regarding these investigations is not in sight.

Sandra Milena states she will defend her son’s memory like a lioness.

“We are standing against a very powerful institution and we have already received very threatening calls,” she texts me before we speak.

She has been sleepless for several days, her cracking voice showing exhaustion. She herself does not know where she has kept so, so many tears. Her only son and her mother, who passed away three years ago, were the two loves of her life. Santiago even witnessed the death of his grandmother, who was ran over by a car, also on the streets of Ibagué. He was never able to recover from witnessing such a traumatic event.

Sandra Milena is very concerned to think that another young person might go out and never return.

“We beg of you, please, in the name of my son: do not allow vandalism to happen, because it can lead to many things. There are many infiltrated agents who want to use my son’s name to cause harm. To the youth who are protesting wholesomely, a piece of advice that I gave to my son: let’s not give them any reason to act, that is what they want, to ignore you and invalidate your arguments. They want reasons to use their weapons against you and then cop out,” she says.

I cannot stop thinking about Janer’s protesting words outside the clinic before the news of Santiago’s decease broke out:

“I’m here, worried about that kid because he isn’t my family, but I know he has a family just like mine, a family that worries, like any of you guys’ families. And I am here to declare, since this has happened, that it’s a very delicate situation and we are not gonna rest, we want this president and this disgusting dictatorship that is ruling over our country to be removed, because we have been living in misery for too long (…) and it’s us, the young people, who are experiencing it. Tax reforms, mediocre presidents that turn their back against their people… that ain’t it, bro.”

A few minutes later, the clinic confirmed Santiago’s death. Sandra Milena felt she also wanted to die right at that instant. And then she broke down, weeping her heart out, and she let out that excruciating and unbearable scream.