Lakes for Water Skiing: The Club in La Calera That Consumes More Water Than Coca-Cola

27 de noviembre de 2025

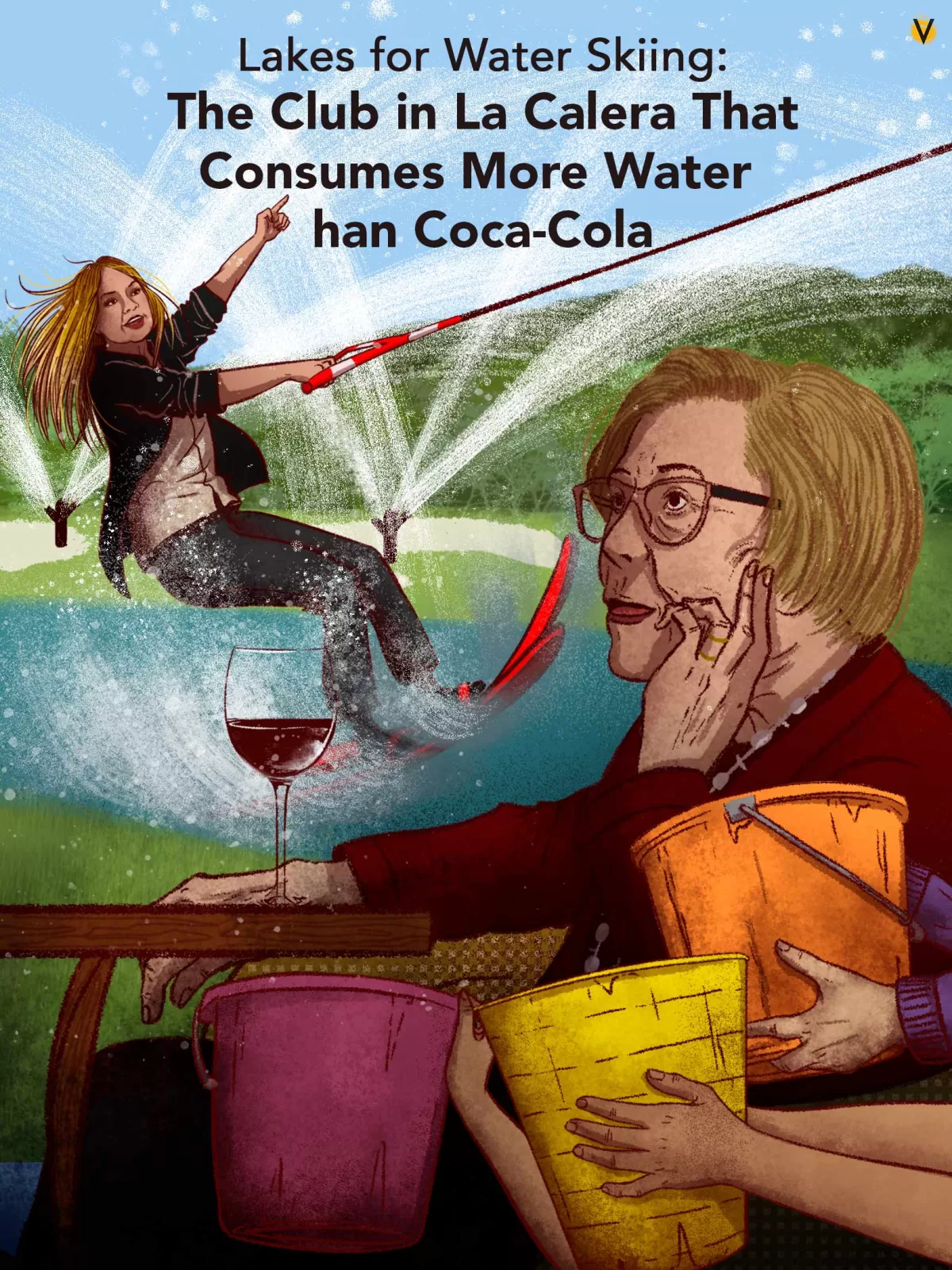

La Pradera de Potosí in La Calera (Cundinamarca) is a residential club where members—or their guests—can water ski, practice equestrian sports, or play golf on green, well-trimmed lawns. Outside the club, on the other side of the road leading to this rural complex, are the houses of the inhabitants of the San Cayetano village. During the drought that lasted from January 2024 into part of 2025, San Cayetano underwent water rationing: for weeks the liquid flowed only between 6 a.m. and 2 p.m. There were even four days when no water came out of the taps. Meanwhile, at the club across the street, people played golf, went water skiing, and rode horses, while households enjoyed a continuous supply of water. In addition, the club’s 25 lakes provided visual enjoyment to the few who manage to enter the place.

Documents from the Regional Autonomous Corporation (CAR) accessed by VORÁGINE show that La Pradera de Potosí captured thousands of cubic meters of water while in La Calera and Bogotá water rationing was imposed. They did this thanks to two concessions, one domestic and one recreational. According to a database that the CAR shared with this media outlet, the club is the third largest water collector in the municipality, surpassed only by the water companies that service hundreds of thousands of people in the area: the Bogotá Water and Sewerage Company and the La Calera Public Services Company. In fact, that residential club accumulates five times more water than the Coca Cola plant located in the Santa Helena district.

The mega-recreational concession that allows La Pradera de Potosí to capture water from three streams is much larger than the concessions granted to several rural aqueducts in the area, which use the water for human consumption. The club paid the government $20,191,000 in 2023 to use thousands of cubic meters of water, while a house in the “stratum three” section of the same village can pay up to $6,818 for each cubic meter.

“I think it’s unfair that water is used for recreational purposes. I’ve been inside La Pradera and I’ve seen how they store water in those lakes; most of them are just for looking at, just for something pretty to look at,” a resident of the San Cayetano village who suffered from water scarcity during the prolonged droughts of 2024 and 2025 told VORÁGINE.

Other events recorded in the CAR files refer to breaches by the club. La Pradera de Potosí pledged to return all the water collected through the recreational concession. However, a report dated July 2, 2024, states: “Although the flow captured from the three water sources is returned to the Teusacá River as a receiving source, because there is no macro-measurement system, it is not possible to determine if 100% of this flow is being returned.” The report also warns that this would be almost impossible, “considering that the water, used for landscaping and recreational purposes, undergoes loss due to evaporation.” In other words, some of the liquid is lost along the way.

This worries Robinson Carvajal, a member of the environmental watchdog group Échele ojito al agua, who says that “extracting water from the area has negative connotations for biodiversity and the maintenance of the ecosystem.” And he added: “This is part of a water privatization process; the water is being captured at one point, is then privatized, and then, in the place where it is discharged, can generate impact,” he added.

Corporate and Political Power

“The person who becomes a partner in La Pradera de Potosí is someone with a lot of money; not just anyone can be part of that community,” Carvajal told this media outlet.

The environmental monitor was unaware of the extent of the water concessions enjoyed by La Pradera de Potosí. To give an idea, while the community aqueduct called the San Cayetano Village Drinking Water Service Management Board is allowed to capture 0.13 liters per second, the residential club has two concessions that add up to 17.49 liters per second, according to data from the CAR report made available to VORÁGINE.

The case of La Pradera de Potosí in La Calera is a telling example of what it means to have access to water in Colombia and is just one of the many faces of inequality. Researchers Sandra Brown and María Cecilia Roa analyzed a database of 28,104 water concessions in the country and concluded: “Concessions appear to be a mechanism of exclusion, since only a minority of users are granted one and the distribution of volume among them is extremely unequal.”

VORÁGINE consulted four sources who all confirmed that the club is home to people like Gloria Pachón, mother of Bogotá Mayor Carlos Fernando Galán, and Vicky Dávila, a right-wing presidential pre-candidate.

The documents that the club submitted to the Bogotá Chamber of Commerce contain the names of the board members between April 2024 and March 2025: Eduardo Calero Arcila, president in Colombia of PriceWaterhouse (one of the four largest financial services firms in the world); Juan Diego Correa, director of Private Banking at Davivienda; Carolina Guillén Gómez, who has served as an arbitrator for the Bogotá Chamber of Commerce, among others.

No Rationing in the Middle of a Drought

La Pradera de Potosí’s concession for domestic use allows the club to draw water from a deep well. In 2015, the CAR initially granted a flow rate of 5.38 liters per second, but in 2021 increased it to 6.49. This aqueduct supplies 373 users.

The club’s water collection volume has been maintained even in contexts where water has been scarce. On January 31, 2024, Noticias Caracol reported the start of rationing in the urban center and some rural areas of La Calera. Months later, on July 10, 2024, the CAR visited La Pradera de Potosí to monitor the domestic concession and the document reads: “based on the deep well, rationing has not been carried out this year.”

A document from the CAR reports that in Pradera de Potosí there was no water rationing during the 2024-2025 drought.

Daniel Piñeros, manager of the La Pradera de Potosí aqueduct, told VORÁGINE that there was no rationing at the club during 2024 or 2025. “This guaranteed supply did not make us indifferent to the general crisis. On the contrary, demonstrating water solidarity, we voluntarily reduced our water collection possibilities and aligned all our operations and internal legal framework with the provisions of general rationing,” he said.

However, the CAR has data that contradicts Piñeros’ version and shows that in La Pradera de Potosí there was no significant water saving at a time when millions of people were forced to ration: from December 2023 to February 2024, the club captured 47,851 cubic meters of water that they extracted from the deep well. In the same period, one year later, the volume totaled 47,147 cubic meters. In other words, the variation was only 1.48%.

Table of water consumption in La Pradera de Potosí between December 2023 and March 2024.

Table of water consumption in La Pradera de Potosí between November 2024 and February 2025, in the middle of the drought and rationing in La Calera and Bogotá.

This data can only be understood in comparison with others. According to an analysis made by Carvajal based on official data, the Public Services Company of La Calera captures 59,616 cubic meters per month for 6,026 users. In a little over three months, La Pradera de Potosí captured the same amount for 373 users.

“The flows captured by La Pradera de Potosí are extremely high; the amount of water used by those people is extremely high. Imagine you have a cube that is one meter on each side; they are using 15,000 cubes a month, it’s a brutal amount,” Carvajal explained.

Figures show that the flow captured by the club is high. For example, the permit granted the Administrative Board of the Drinking Water Service of San Cayetano Village, which allows the collection of a flow of 0.13 liters per second, supplies 77 users. In other words, the permit for La Pradera de Potosí is 49 times larger than that of the Administrative Board, even though it only supplies a population 4 times larger.

The Association of Users of the Rural Aqueduct Vereda el Manzano Quebrada la Chucua in La Calera has 103 users and a concession of 0.11 liters per second. In other words, La Pradera de Potosí captures 59 times more water to serve slightly more than three times the number of users.

Piñeros, who answered a questionnaire via email, gave his version of the water consumption levels at the club: “Despite serving a considerable resident population (342 homes), the 2,600 club members, 430 employees and more than 15,000 monthly visitors, our per capita consumption indicator is comparable to the averages of cities like Bogotá, which indicates a rational and responsible use of water.”

Although the number of concessions for domestic purposes is high, the number for recreational purposes is almost double that.

Water Skiing and Other Needs

La Pradera de Potosí occupies an area of 109 hectares (270 acres). Anyone with the money or the necessary connections can enter and enjoy a flowery, aquatic landscape with various animal species. A “Guide to the Flora and Fauna of La Pradera” contains an inventory of the wildlife in the place: blackbirds, canaries, partridges, toches, troupials, herons, opossums, coatis, foxes, butterflies, frogs, trout, hydrangeas, bougainvilleas, lilies, dahlias, magnolias. This is thanks to the club’s 25 lakes.

These bodies of water are also ideal for the 18-hole golf course, which is one of the club’s major attractions. The La Pradera de Potosí website promotes it like this: “The wide, undulating greens, the broad fairways bordered by a demanding kikuyu rough, the 94 bunkers, and the 16 artificial lakes, are complemented by the movement and curves that make this course one of the most spectacular in the country.”

A green is the area surrounding the hole where the ball must enter. A fairway refers to the expanse of grass between the teeing ground and the green. The roughs are the areas outside the golf course, with longer grass, where the ball sometimes ends up, and kikuyu is a type of grass favored by golfers because it is dense and raises the course’s level of difficulty. The 16 artificial lakes were created thanks to the aforementioned concession.

Another of the lakes is reserved for water skiing. The club’s website contains some details about this body of water, which can only be enjoyed by its members or guests: “The lake has four regulation tracks for slalom, tricks, jumping, and wakeboarding, and has a length of 570 meters, an average depth of 1.80 meters, a width at the narrowest point of 55 meters, and at the widest point of 180 meters.”

To have bodies of water of that magnitude, it is necessary to capture equivalent amounts of liquid. We secured information on the subject through a petition that VORÁGINE submitted to the CAR. The file we received reveals that on November 30, 2017, the CAR issued a concession for La Pradera de Potosí to capture 12 liters per second from three streams: El Asilo, La Pradera, and Granada. The current extraction permit is for 11 liters per second.

Even during the worst moments of the drought, when a red alert was declared in La Calera, the club did not stop collecting water to fill the lakes. A report known to this media outlet, dated July 2, 2024 (three months after rationing began in La Calera), reads: “taking into account the low levels of the water sources, they have not suspended service.”

This CAR document demonstrates that during the drought, La Pradera de Potosí continued to capture water for recreational purposes.

“We are quite concerned about how water is allocated, for what uses, and obviously who ‘enjoys’ the water when others do not have access to it for basic needs,” Carvajal said. “The legislation is very clear: water for human consumption is prioritized over other uses,” he added.

During the drought, the flow of water captured by the club did decrease, but this would have been due to the scarcity of water and not a voluntary decision. The same report from July 2024 states: “it was found at the time of the visit that the diverted flow is less than the one granted corresponding to 4.5 liters per second, this as a result of the summer (dry) season.” Further on it says: “Water sources have shown variations in their supply, levels, and flow rate due to the summer (dry) season.”

Piñeros defends the recreational use that the club enjoys: “La Pradera de Potosí’s water concession does not constitute an act of privatization of the resource. This is a temporary use permit for a public and national asset (water) that is subject to monitoring, control, and compliance with the conditions imposed by the environmental authority (CAR).” He even stated that the local lake system helps to “mitigate the risk of flooding and rising water levels in the area.” In October 2022, the club was flooded because the level of one of the streams rose.

The manager of the La Pradera de Potosí aqueduct also assured that they are guaranteeing the return of more water than they capture from the three streams through the concession. He said that to ensure this they had to import specialized equipment in 2024. “This technology has made it possible to quantify the total return of the resource. Thanks to the high rainfall in the area where La Pradera de Potosí is located and the collection capacity of our lakes, we have verified that the flow of water returned to the ecosystem is greater than 100% of the flow captured from the surface source. This ensures regulatory compliance and demonstrates our transparency and positive water impact in resource management,” he concluded.

Little Willingness to Save

The drought had been going on for several months when the CAR issued a technical opinion on May 10, 2024, regarding actions for efficient use and water conservation in La Pradera de Potosí. The document noted certain inconsistencies: “Non-compliance with rainwater harvesting and water reuse activities (…) Non-compliance with measurement activities (…) Costs of the efficient use and water saving program: they do not present an executed budget for each of the proposed activities.”

The CAR drew attention to several instances of non-compliance by La Pradera de Potosí with respect to water conservation initiatives.

The above showed that the club was not taking any action to use rainwater or to reuse water, two important actions in a place where, for example, there are 18 tennis courts, a service station, and an automotive workshop.

From Piñeros’s response to VORÁGINE, it can be deduced that these inconsistencies have not yet been corrected: “We are currently conducting feasibility studies to implement complementary methods that will significantly increase the percentage of rainwater reuse.”

The four people from the surrounding communities that we interviewed for this article were surprised when they learned about La Pradera de Potosí’s water catchment levels. Carvajal warned of the possible long-term consequences of improper management of the precious liquid: “If we do not secure the amount of this resource for the future, we could have shortages where –– unlike last year when we had a year of rationing–– we could expect rationing for much longer periods.”

Water in the village of San Cayetano in La Calera will continue to flow constantly so that the members of La Pradera de Potosí and their friends can enjoy a peaceful landscape with animals, lakes whose surface is barely touched by skis, and bodies of water filled with the golf balls of unskilled players, while on the other side of the street, people pray for the drought not to return, and with it, their thirst.

Read also: La Calera: Water for Coca-Cola and Bogotá, but not for Its People

If you would like to share more information with us on this or other topics, please write to: nicolas.sanchez@voragine.co

* This content is funded by support provided, in part, by Vital Strategies. Content is editorially independent and its purpose is to shine a light on both the food and beverage industry illegal or unethical practices and the Colombian most vulnerable populations, who disproportionately bear the brunt of the global health crisis resulting from the unhealthy food and beverages consumption. Unless otherwise stated, all statements and materials posted on this article, including any statements regarding specific legislation, reflect the views of the individual contributors and not those of Vital Strategies.