Compotas San Jorge and the Tricks Played by Ultra-processed FoodProducers to Avoid Warning Labels

22 de agosto de 2025

There’s a well-known saying in Colombia: “Once the law is made, the trap is set.” Some companies producing ultra-processed foods and sugary drinks seem to be applying this maxim, leading to a tragic disregard for common standards of living in society.

VORÁGINE discloses cases of certain companies’ non-compliance with mandatory labeling of products containing excessive sodium, sugar, or fat. The use front-of-package warning labels intended to provide consumers with clear information is allegedly being evaded by companies selling certain sugar-laden baby food, soda, and other products. The findings highlight the challenges facing implementation of the law requiring companies to warn consumers about the presence of excess amounts of components linked to the development of diseases.

This media outlet learned of a complaint filed by the NGO Red Papaz against the company Levapan. The company’s name is unknown to many, but its ultra-processed food brands are easily recognizable to Colombians: San Jorge sauces, Gelhada gelatins, among others.

Red Papaz’s filed their complaint on June 25 with the National Institute for Food and Drug Surveillance (INVIMA), the entity responsible for enforcing the regulation requiring front-of-package warning labels. The NGO warned the organization that one of Levapan’s products —a compote marketed for children— would place the company in violation of the law.

The San Jorge brand’s “Apple Compote” is promoted on the company’s website as “a complement to breast milk.” A look at the nutrition facts panel reveals that the compote contains 12 grams of added sugar, and should therefore be packaged with a warning label, which is nowhere in sight.

The printing of warning labels is a public health measure recommended by organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). The latter has stressed: “Front-of-package labeling is a simple, practical, and effective tool for informing the public about products that can be harmful to health and for helping guide purchasing decisions.”

Regarding the relationship between children and products with excess sugar, sodium and saturated fats, Unicef issued a report which pointed out: “Childhood obesity and a diet high in ultra-processed foods have lifelong health consequences and increase the risk of non-communicable diseases (NCDs), including heart disease, diabetes, and certain cancers, which increase morbidity and mortality.”

Despite all the public health recommendations, the industry devoted significant resources to lobbying against front-of-package labeling and taxes on sugary drinks and ultra-processed foods. VORÁGINE told these stories in “122 Visits to Congress: How the Postobón Lobbyist Opposed the “Healthy Taxes”“ and “Lobbying Disguised as Science: Academic Associations Defending Junk Food“.

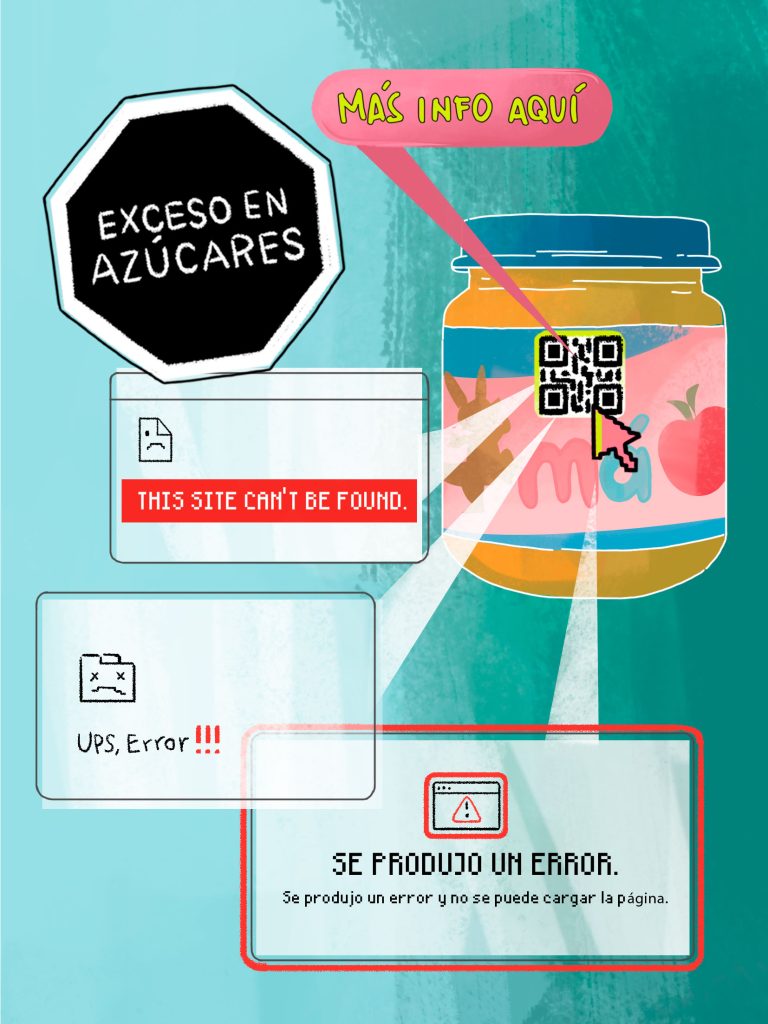

The resolution regulating front-of-package labeling in Colombia contains provisions that have been used by some companies to evade their responsibilities. For example, labels with an area of less than 30 cm2 need not include warning labels; instead, links or QR codes must direct consumers to the labels which the product is obligated to display. This is the case of the San Jorge Apple Compote.

The problem, according to Red Papaz, is that the link Levapan placed on the compote label was broken. It didn’t lead to a webpage with the “excess sugar” warning. The link was simply useless, as evidenced in the screenshot attached to the lawsuit.

In the words of the complaint filed by Red Papaz (to which INVIMA has yet to respond): “Although the product seems to formally comply with the inclusion of a link or a QR code, because the link provided is not functional (…) it does not materially fulfill the objective that the regulation intended, which implies a real and effective violation of the right of consumers to have accessible, understandable, and verifiable information when purchasing the product.”

VORÁGINE called Levapan on July 17 and requested an interview with a company spokesperson to discuss front-of-package labeling. That same day, we confirmed that the company had made the link printed on the compote’s label once again functional. “At Levapan, we have processes in place to periodically audit and verify that all links are working; however, at this time, the link printed on the product label may be operating intermittently,” the company’s press office explained in response to questions from VORÁGINE. However, to access the warning, the consumer has to search for the product among a series of options and click on it.

It is difficult to know how many consumers visit websites or use QR codes to access warning labels. A study by the Universidad Complutense in Madrid found that a supermarket customer takes only 25 seconds to decide what item to buy.

With regard to the compote, which San Jorge sells as a complement to breast milk, we consulted Juan Camilo Mesa, nutritionist, dietitian, microbiologist and Master in Nutritional Sciences. He confirmed that compotes are unnecessary, but if parents choose to give them to their children, they can make them themselves, without sugar. The San Jorge compote contains 12 grams of sugar. “There is a linear relationship between sugar consumption and the development of diseases. It’s very similar to alcohol in that no “safe” amount exists, meaning the less the better,” he said. Mesa.

Other Ultra-processed Food Companies with Similar Practices

Red Papaz has been tracking how companies are implementing front-of-package warning labels. Aside from what’s happening with Levapan, they’ve discovered that other companies have resorted to gimmicks that prevent consumers from easily accessing information.

One example is the 400-milliliter sugary drink called Del Valle Fresh, a product whose label size requires a printed link or QR code directing consumers to warning labels. When opened, the QR on the product leads to www.coca-cola.com. In other words, the consumer is directed to advertising and not nutritional information informing of an excess of critical nutrients.

“They are preventing front-of-package warning labels from fulfilling their purpose of informing people, of providing clear, truthful, sufficient, immediate, and visible information,” said Lina Cerón, coordinator of the Red Papaz Food Project. “The supposed linking to the label via a QR code is quite problematic,” said Adriana Torres, economics coordinator for DeJusticia, another NGO that has been following the issue.

Both confirm that, following enactment of the decree mandating front-of-package warning labels, they began to observe sugary beverage companies like Postobón and Coca-Cola releasing smaller presentations of their products. “These smaller sizes mean smaller labels, which allows them to use a link to a website or a QR code instead of the warning label,” Cerón said.

Torres added that they have also observed another practice in supermarkets and neighborhood stores aimed at reducing the effectiveness of the warning labels. “We’ve discovered that the warning labels are sometimes hidden in their presentation on shelves,” she said.

Micro-labelling and Controls: Possible Solutions

It was foreseeable that the front-of-package warning label regulations would present various challenges when it came to implementation. As VORÁGINE has documented extensively, certain sectors of the industry were determined to lobby against the public health measure.

Warning of the potential ineffectiveness of links to websites and QR codes, Red Papaz submitted a request to the Ministry of Health on April 11, 2025, proposing a measure to correct this gap in the law and the resolutions that regulate it. The document, reviewed by VORÁGINE, contains a list of products that are not displaying warning labels due to the size of their labels, including 400ml Pepsi, Compotas San Jorge, Mr. Tea, certain Postobón sodas, and others.

The NGO presented Minister of Health Guillermo Alfonso Jaramillo with a proposal to create “micro-labels.” In the proposal, products with labels smaller than 30 cm2 would carry octagonal seals with a number inside indicating the amount of excessive critical nutrients in the product. Red PaPaz argued that this is how it works in countries like Mexico and Argentina.

In a response that came on April 25, 2025, the Ministry denied, for the time being, the possibility of changing the regulations to include micro-labels. The Ministry argued that it is necessary to wait five years —from 2021 forward— before evaluating the impacts of the labels, and to make modifications.

DeJusticia’s Torres believes that strict control of the provisions contained in the law is the best path to follow. “Before reconsidering a resolution of the reform, we must strengthen the monitoring and control mechanisms,” she added. “The mechanisms for monitoring and controlling labeling need strengthening, specifically in cases where the warning label is not visible, but instead directs you to a website or a QR code.” INVIMA is the entity in charge of monitoring and control, but the entity’s capacity to effectively oversee the sanctioning of offenders would be limited. INVIMA responded to a petition filed by VORÁGINE with information confirming that only three companies have been sanctioned for non-compliance with provisions regarding front-of-package labeling.

Reformulation: Another Deviation from the Norm

Another issue has generated concern among social organizations that monitor front-of-package labeling. There is evidence that some companies are switching ingredients that would require labeling for others that do not require labels, but that, in excess, can also be harmful to consumers’ health.

Cerón added that in Africa a concept has evolved with regard to this industry practice, which has been spotted in various places around the world: reformulation without a public health focus. “There are a number of different chemical additives that perform salting, preserving, or sweetening functions. The industry has begun reformulating using these additives, with no interest in public health and without improving the product. They’re using chemicals with very strong effects on health and that, when consumed in excess, are even more harmful than the critical nutrients,” he said.

Nutritionist Mesa gave an example of reformulation: “The brand Margarita increased the calories —because you can play with that— in order to remove warning labels from their potato chips.” He explains that he has seen cases where a package of potato chips can have the same calories as an adult’s lunch. “We need an excess calorie label because the industry is taking advantage of that (…) If we consume more calories than necessary, we’re going to have a public health problem,” he said.

Warning Labels: An Important Measure That Calls for Others

The three people interviewed for this article agree that front-of-package warning labels have been a very important public health measure. Cerón emphasized that, in meetings with the Ministry of Health, the agency has reported a decrease in the consumption of ultra-processed foods and sugary drinks.

“I believe the public is much more aware of the effects of consuming ultra-processed foods than four or five years ago, when our discussions on this issue grew more intense. “I think the conversation has evolved and we’re now at a different level of citizen awareness,” Torres said.

Front-of-package warning labels are just one public health measure that should be accompanied by others. “We need healthy school environments, restrictions on advertising, and guaranteed access to real food,” Torres said.

Healthy school environments refer to restricting the sale of soft drinks and ultra-processed foods in schools. As for advertising restrictions, this means that the companies that manufacture these products cannot create promotional pieces that target children and adolescents. These measures have been proposed in Congress, but have ultimately been dropped due to industry lobbying or a lack of interest from parliamentarians.

Guaranteeing access to real food refers to state actions that seek to prioritize products that are not ultra-processed. “We need the School Meal Program (PAE, for its Spanish acronym) or the various ICBF (Colombian Institute of Child Welfare) food assistance programs to promote real and locally-produced meals. This would allow us to intervene in the environments where children spend the most time and foster healthy eating habits,” Torres explained. “We need public policies that address the right to food from a perspective of the entire food process, from seed to plate,” she concluded.

The greatest opposition to public health policies regarding ultra-processed foods has come from the major players in the food industry. The front-of-package labeling legislation, even with the current gaps, managed to pass. Organizations promoting measures like this hope to once again circumvent the corporate lobby to broaden the policies needed for healthier eating. It’s a global debate, and it’s happening right now in Colombia.

* This content is funded by support provided, in part, by Vital Strategies. Content is editorially independent and its purpose is to shine a light on both the food and beverage industry illegal or unethical practices and the Colombian most vulnerable populations, who disproportionately bear the brunt of the global health crisis resulting from the unhealthy food and beverages consumption. Unless otherwise stated, all statements and materials posted on this article, including any statements regarding specific legislation, reflect the views of the individual contributors and not those of Vital Strategies.