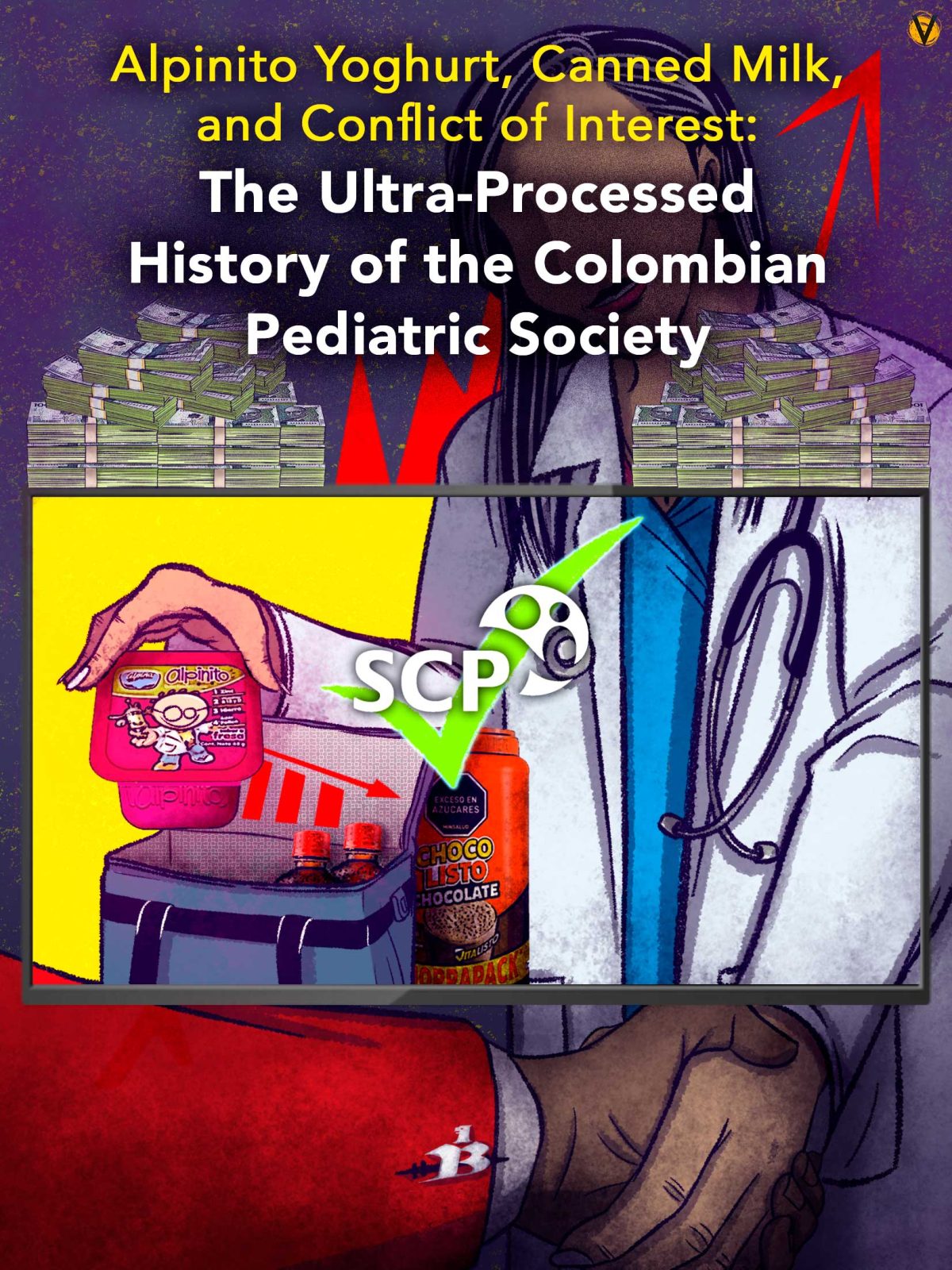

Alpinito Yoghurt, Canned Milk, and Conflict of Interest: The Ultra-Processed History of the Colombian Pediatric Society

15 de julio de 2025

—If this continues, in two years the Society will be bankrupt.

Pediatrician Juan Fernando Gómez issued this warning after a concerned reading of the financial report of the Colombian Pediatric Society (SCP, for its Spanish acronym). On May 15, 2004, as president of the organization, Gómez called a meeting of the board of directors for 8:30 a.m. at the Club Almirante Colón in Bogotá. The SCP had been looking for ways to achieve sustainability for several years, but their income was insufficient. Although the organization held a bi-annual congress, had created a magazine that allowed them to sell advertising space, and designed courses to sell to pediatricians… it still wasn’t enough.

In 2002, the board of directors—a group of physicians elected by other physicians—approved the hiring, for the first time, of a manager to provide the organization with financial direction. They found Gloria Helena Zuccardi Hernández, a business administrator from Barranquilla who had been working as a commercial executive at Bancóldex, a state-owned bank that promotes businesses.

The day she was hired, Zuccardi introduced an idea that became a key precedent of how, despite criticism, conflicts in the SCP between the search for money and the preservation of ethical principles began to be resolved in favor of money. Zuccardi proposed a deal with Bavaria to promote the inclusion of Pony Malta in children’s lunchboxes.

***

This story could be told as a business success story. The story of a company that once saw its numbers in the red and achieved prosperity through bold management. But the SCP is not a company; it is a non-profit medical and scientific association. And the management in question that stayed off bankruptcy has been propped up for the last 25 years, in large part, by deals that called for the relaxation of the board’s ethical principles in exchange for funding from the ultra-processed food and beverage industry.

And deals have continually been made with the pharmaceutical industry as well. Dealings with both these industries are problematic because of what they mean in terms of independence for a scientific society that advocates, in its statutes, for the health of children and adolescents. But the case of ultra-processed foods is particularly sensitive, as it has turned the SCP into a partner and promoter of an industry dedicated to selling products with very poor nutritional value. These products now carry labels warning of excess added sugars, sodium, and trans and saturated fats, which can contribute to the development of obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease if children do not consume them in moderation.

At the same time, the SCP maintains an unquestionable commercial relationship with the companies that manufacture well-known brands of infant formula and canned milk, promoted with strategies questioned worldwide, and in Colombia, given that they are contrary to the promotion of breastfeeding, a practice currently losing ground in Colombia. In fact, the SCP makes it easier for these companies to attract doctors with gifts. In return, the industries help fund conferences and symposia organized by the SCP, creating a link that contravenes scientific and World Health Organization recommendations.

These types of negotiations are of public interest as scientific societies often serve the government, Congress, academia, and the media as a source of rigorous and independent information in public health debates. The SCP is, in fact, promoted as a government advisor “on the development of policies in favor of children”.

In 2024, and far from bankruptcy, according to its most recent reports, the SCP recorded the fifth largest income among the 70 medical organizations that make up the Colombian Association of Scientific Societies. It billed 6.556 billion COP (with surpluses of $900 million), coming in right below the Endocrinology, Orthopedic Surgery, Hematology and Cardiology associations.

Although the boon is attributable to various sources of funding, the story of the SCP’s financial solvency over the past 25 years is impossible to tell without mentioning the role played by the ultra-processed products and infant formula industries.

More stories related to this topic: Todo Rico’s “Little Trick” to Avoid Warning Labels

“Can anyone confirm that Pony Malta is bad?”

It was Executive Director Gloria Zuccardi who proposed a business agreement with Pony Malta at the 2004 board meeting, but the idea of working with the ultra-processed food industry was hardly new to the SCP. The organization, founded in 1917, already had relationships by the late 1990s with several companies that were playing hardball in that area.

In 1999, for example, the then president of the SCP, pediatrician Jorge Eduardo Loaiza, presented a management report in which he stated: “Training sessions have been possible thanks to contracts we have signed with companies such as Kimberly Colpapeles and Nestlé, following a recommendation made by the IPA (International Pediatric Association) at a meeting held in Hong Kong in 1997, stating the need to make financial agreements with private companies in order to increase management capacity in our work. To this end, we’ve met with the Santodomingo Groups [then owners of Bavaria] and Ardila Lülle [owner of Postobón] and with the Kellogg’s and Alpina brands. We are currently in talks with the Compañía Nacional de Chocolates.”

Zuccardi’s achievements as executive director, along with those of the majority of pediatricians who have served as President and on the SCP’s boards of directors, reflect a deepening of that philosophy.

And she took a very important step on May 15, 2004, when the outlook was bleak. As background, the directors of the Bogotá chapter of the SCP, known as the Bogotá Regional, had signed a commercial agreement with Bavaria to promote Pony Malta in schools across the city. What Zuccardi did in the meeting was propose to the board of directors to expand that agreement so that it would be implemented not only by the Bogotá Regional, but by the SCP as a whole. Zuccardi presented it as “a proposal that Pony Malta be included in children’s lunchboxes twice a week instead of soft drinks.”

Doctor Rafael Castro, a board member who was informed of this decision, toned down the proposal to make it sound less indecorous to a group of doctors: “Rather than a campaign to put Pony Malta in lunchboxes,” he said, “it’s about carrying out a campaign to inform parents about how to ensure good nutrition for their children.” He explained that Bavaria would pay $130 million COP to the SCP (about $315 million COP today) and would cover the costs of lectures on good nutrition given by pediatricians in schools in major cities. In return, Bavaria would circulate a promotional video for Pony Malta mentioning that the soft drink had the SCP’s endorsement.

Bavaria had spent decades positioning Pony Malta as a healthy and nutritious drink for children. Famous athletes appeared in their commercials, happily drinking the soft drink in the brown bottle: “The drink of champions!” read the slogan. Today, the same strategy is maintained, although it is public knowledge that Pony Malta is an ultra-processed soft drink that is not nutritious and is full of sugar.. This is why the famous bottles with the logo of a bucking pony now carry a black warning seal, following the front-of-package warning label law passed by Congress in 2021.

At the time of the 2004 meeting, the debate over ultra-processed foods and sugary drinks wasn’t on the table in Colombia, but that doesn’t mean that the doctors at that meeting didn’t know what Pony Malta really was. Or at least some of them.

Dr. Castro—who, along with manager Zuccardi, was the main driving force behind the proposal—told the board that they had visited the Bavaria plant, “where they were able to observe the quality and rigor of the manufacturing process and learn about the benefits of the product, which is low in protein but high in calories.”

“We must make it clear that this campaign can be very beneficial to the community, as it aims to spread knowledge about good nutrition,” insisted Dr. León Jairo Londoño, secretary of the SCP. Besides, it would be economically beneficial for the SCP.

The money factor thus entered the discussion, where the voice of Dr. William Parra, also on the board, rose as the most dissonant:

“Society must be very clear about the difference between a good deal and good business,” he said. In this campaign, we’ll be promoting the use of Pony Malta to replace yogurt or other more nutritious foods.

“We must recognize that a product is being endorsed, one with significant risks that require debate,” warned Dr. Hernando Villamizar, vice president of the SCP. We are promoting it as a substitute for other products that may be equal or better from a nutritional point of view, and which may be less expensive.

“Pony Malta is better than some other products, like colas and other beverages,” Dr. Castro insisted.

“I wouldn’t sign up to give a talk on children’s nutrition alongside a nutritionist who’s talking to parents about the importance of Pony Malta in their lunchboxes,” said Dr. Juan Fernando Gómez, president of the SCP.

But manager Zuccardi brought money back into the discussion:

“I’m no expert on nutrition,” she clarified, “but I think the SCP would have a presence in the community with its healthy eating campaign.” To which the economic needs of the SCP should be added, without violating ethics.

“Can anyone confirm or say that Pony Malta is bad or harmful?” asked Dr. Londoño, secretary of the SCP, to emphasize the point.

The discussion revealed significant reservations, but they agreed not to refuse the deal with Bavaria and, instead, to impose certain conditions, such as clearly defining the content of the video that the company would release about Pony Malta and not using it extensively outside of the campaign. Dr. Parra, who had asked to “raise money, but in an ethical manner,” demanded that his negative vote be recorded in the minutes.

A year later, at the 2005 general assembly (the SCP’s most important meeting given that it approves financial statements and changes to bylaws, and discusses the organization’s direction), some pediatricians demanded accountability for “the Pony Malta program.” Presentation of the program had begun in cities like Bogotá and Barranquilla, but criticism from SCP-affiliated doctors in several regions led to its suspension, Zuccardi herself reported, according to the minutes. However, that did not negate the fundamental point: the creation of a system of endorsements through which, in exchange for money, the SCP would put its logo on different products, including cooking oils, soaps, and diapers.

On that day in 2004, when the board of directors held an extensive discussion about the Pony Malta agreement, an endorsement committee was formed in which doctors from the same board would be responsible for studying each decision.

In a written response to this investigation, the SCP told VORÁGINE that “around the first decade of the 2000s, certain food products were endorsed based on the nutritional criteria of the time.” The discussion about Pony Malta, however, reveals that these criteria did not generate consensus among the organization’s pediatricians, that there were reasonable doubts, and that, in any case, the need for funding was a factor in the decision. A source familiar with the workings of the endorsement committee spoke confidentially to VORÁGINE, saying that no technical or scientific studies were ever conducted, as the money factor took precedence.

An endorsement from the SCP was a valuable boost for the marketing strategies of ultra-processed food companies, as it provided their products, without rigorous evaluation of the nutritional benefits, a scientific legitimacy that they could exploit in television commercials, on supermarket stands, and, as Alpina did at the time, in their sustainability reports.

The first steps toward endorsing ultra-processed foods as a source of financing were taken in 2002, when the SCP signed a contract with Alpina to promote the “Baby” line of products that the company had just launched. This business relationship lasted about 15 years (far beyond “the first decade of the 2000s” that the SCP mentions). In 2017, for example, Alpina ran television commercials like this one about Alpinito, promoting the product as another ingredient in a lunchbox to “support the growth” of children. And with the final note: “the only one recommended by the Colombian Pediatric Society.” Today, due to the labeling of food and beverage products, it is public knowledge that Alpinito yoghurt contains excessive added sugars and saturated fats.

McDonald’s —an ally of Alpina— used the endorsement to promote the inclusion of Alpinito yoghurts in its Happy Meal (which includes a choice of fried chicken nuggets or a hamburger with fries) with the message that it was “The perfect balance between nutrition and fun for its littlest customers.”.

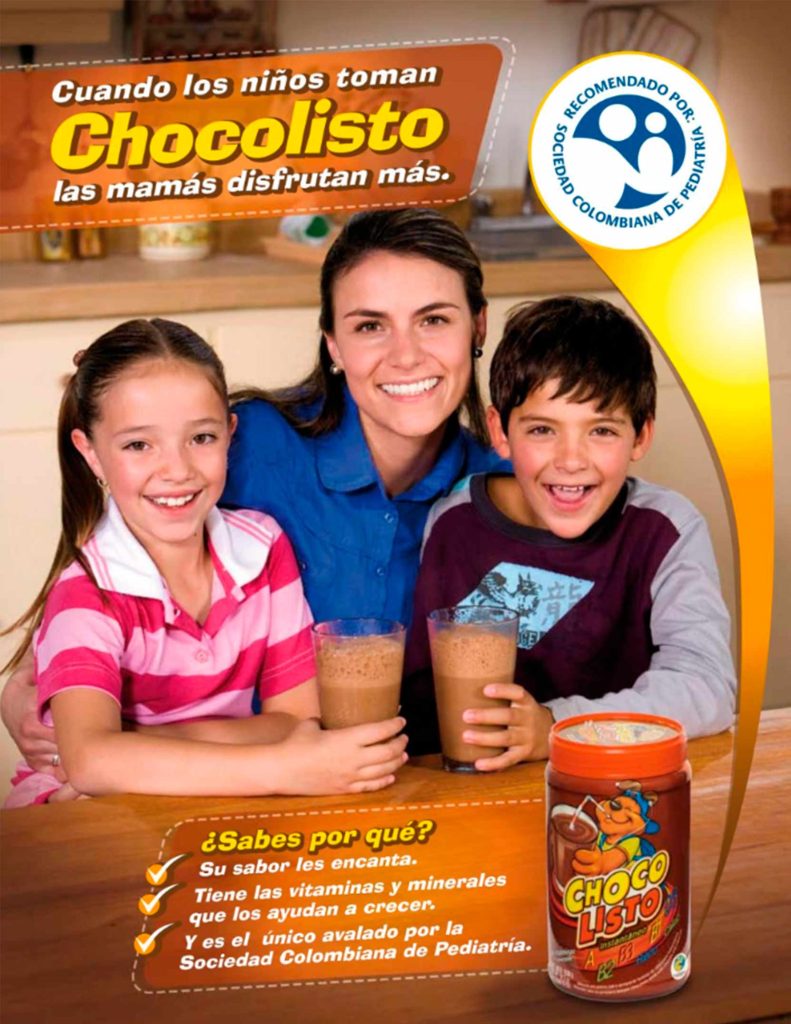

The SCP also endorsed Chocolisto (a Nutresa product currently sold with the excess sugar warning label), which allowed the brand to use advertisements like this one from 2011, in which the scientific society’s logo occupies a prominent space, in the upper right corner:

The industry not only took advantage of the endorsements to circulate these types of messages in mass media; the SCP also welcomed them, for two decades, in the pages of its magazine, Parenting and Health, the specialized publication created for pediatricians and parents and, therefore, found in any pediatrician’s waiting room. In it you’ll find advertisements for Alpinito and Chocolisto, as well as other products with no endorsement, but whose companies paid for the advertising. In 2011, for example, although there was no longer an agreement with Bavaria to promote Pony Malta in lunchboxes, the magazine featured ads like this one highlighting the soft drink’s “nutritious energy”, alongside information on child-rearing.

The minutes of the SCP associates’ meetings are proof that, for years, some pediatricians raised their voices to warn of the inconsistency that these business dealings represented for an organization that claimed to work for children’s health.. At the 2009 general assembly, for example, Dr. Álvaro Posada from Antioquia said that “Colombian children and families are being trampled upon by (advertisers) asking them to buy this or that product, and many, it is assumed, are endorsed by the SCP.”

But the minutes also show that the endorsements and advertising of ultra-processed products in the organization’s publications had grown to represent a decisive factor in its accounting. In the early years, Director Zuccardi and the different presidents expressed concern when the number of endorsement deals decreased. Later, it was the other way around. At the aforementioned meeting in 2009, the then president, pediatrician Hernando Villamizar—who had warned of the risks of endorsing Pony Malta at the 2004 board meeting—took pride in a balance sheet showing that “every day we earn more and spend the same amount.” Zuccardi seconded him by showing the pediatricians that, following the “lean years”, the financial statements reflected surpluses for the second consecutive year. In response to Posada’s complaint, President Villamizar responded: “I hope the day comes when the SCP no longer needs to make these endorsemens.” It wasn’t until 2018 that those endorsements came to an end. Today, the SCP no longer endorses any ultra-processed products. Abandoning them meant finding other sources of income, such as marketable pediatric publications, partnerships, and new events. But this hasn’t kept the organization from engaging in business ventures that create conflicts of interest or are inconsistent with its mission of defending children’s health. They have, in fact, remained an ally of the ultra-processed food industry, once again amid criticism from a segment of the organization’s affiliated pediatricians. The discussion no longer revolves around soft drinks or edibles like Alpinito, but rather around infant formulas.

SCP’s Gifts to the Industry

The questions raised by the SCP’s relationship with the infant formula industry have come to light in the international context that has been building for 40 years.

Any pediatrician, to begin with, should know that there is scientific consensus that breast milk is the best food for a baby and that, under normal circumstances, it should be the child’s exclusive food until the age of six months. From then on, “children should begin eating safe and appropriate complementary foods while continuing to breastfeed for up to two years or more,” says the World Health Organization. And they add: “Breastfed children perform better on intelligence tests, are less likely to become overweight or obese, and, later in life, to develop diabetes.”

The decision to give a baby formula (liquid or powdered milk generally made from cow’s milk, sometimes soy) should be based solely on medical advice and made in exceptional situations, when required by “a small number of the newborn and the mother’s health conditions.” says the WHO. For this reason, these milks have also been technically called breast milk substitutes, to indicate that they can replace breast milk. They are marketed to feed babies and children up to three years old, and brands such as Nestlé, Mead Johnson, Abbott, Nutricia, Alpina, Máh! and Sanulac, among others, are sold in Colombia.

The “Stop Eating Lies” campaign, which was created by the Red Papaz organization and analyzes the ingredients in products sold by the food industry in Colombia, classifies infant formulas as ultra-processed to which “substances are added that could affect” the health of children. Therefore, although formula milk can save lives in rare cases, it is recommended that its consumption be exceptional.

And, two years ago, in February 2023, a group of scientists published in the influential scientific journal The Lancet a series of articles that included an in-depth review of the “abusive tactics of the infant formula industry” around the world. The industry, they concluded, has grown thanks to monumental marketing strategies that have been imposed to the detriment of breastfeeding rates. Among the studies they cited was one based on data from 126 countries which concluded that “for every additional kilogram of standard formula (formula made for infants 0-6 months) sold per child each year, breastfeeding decreased by 1.9 percentage points.”

This despite the fact that the WHO adopted a code in 1981 seeking to regulate the industry’s promotional strategies so that mothers do not stop breastfeeding their babies in exchange for formula milk. The code, known as International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes, remains the guiding beacon on this issue. Colombia adopted it in 1992 through a decree now practically forgotten.

The Code established, among other things, that advertising should not idealize these milks, but should warn of the risks of unnecessary consumption. And that, to promote their products, manufacturers must not offer “financial or material incentives to health workers” (doctors, nurses, nutritionists) or their family members, nor should such incentives be accepted by health agents or members of their families.”

The WHO has continuously reinforced that mandate with recommendations over the past four decades so that, to prevent a drop in breastfeeding rates, industries that market products for children do not sponsor meetings of health professionals. They also recommend that doctors and medical associations do not allow these industries to fund their events.

In other words, there is a global institutional and scientific appeal—which, although it does not have the force of law, is understood as an ethical mandate—to prevent the infant formula industry, with the reach and power granted by its multi-million-dollar profits, from coopting pediatricians to the point that they end up prescribing formula milk unnecessarily. But the scientists who took stock for The Lancet reported that, “in the absence of other funding, professional associations in medicine, midwifery and nutrition continue to accept sponsorship from manufacturers (…) even when the companies are known to be violating the Code.”

This is the case of the Colombian Pediatric Society.

For about ten years now, the number of events organized by the SCP has grown steadily. For decades, the National Pediatric Congress, held every two years, was virtually the only major gathering of pediatricians in Colombia. Today, the SCP also organizes the International Symposium on Pediatrics, the National Congress on Nutrition, the Latin American Congress of Pediatric Residents, the National Congress of Pediatric Residents, and even a meeting held not only for pediatricians, called the World Health Conference.

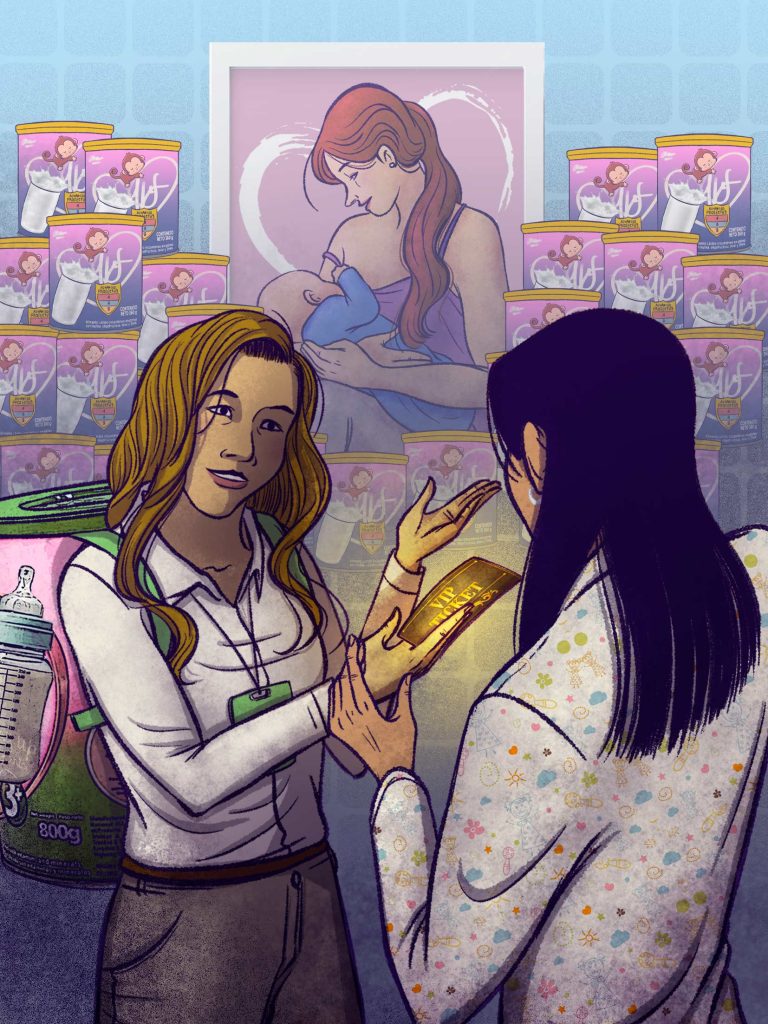

The SCP sells pharmaceutical companies and companies that manufacture infant formulas space at these events in which to promote their products. This money pays the bulk of expenses for organizing each meeting. In return, the SCP allows them to promote products, such as infant formula, to attending physicians. Here, for example, is a photo of an Alpina team promoting the company’s formula at the 2024 International Symposium on Pediatric Updates. The photo was posted by a subsidiary of Alpina on social networks.

And here is the multinational Mead Johnson’s stand promoting one of its brands of infant formula at the 2015 National Nutrition Symposium (the photo was published by the SCP itself on their website):

Although this is already problematic in light of the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes and the WHO recommendations, today the SCP goes further: When you sell a company space at a conference, you also provide them with —depending on the size of the stand— a certain number of free registrations for that company to give away to pediatricians. In other words, the SCP encourages the industry to provide in-kind incentives to physicians, which can be very attractive.

A pediatrician with firsthand knowledge of these SCP incentives —and who asked to speak confidentially— put it this way: “The SCP guarantees that Nestlé or any other company can tie me down with their gifts.”

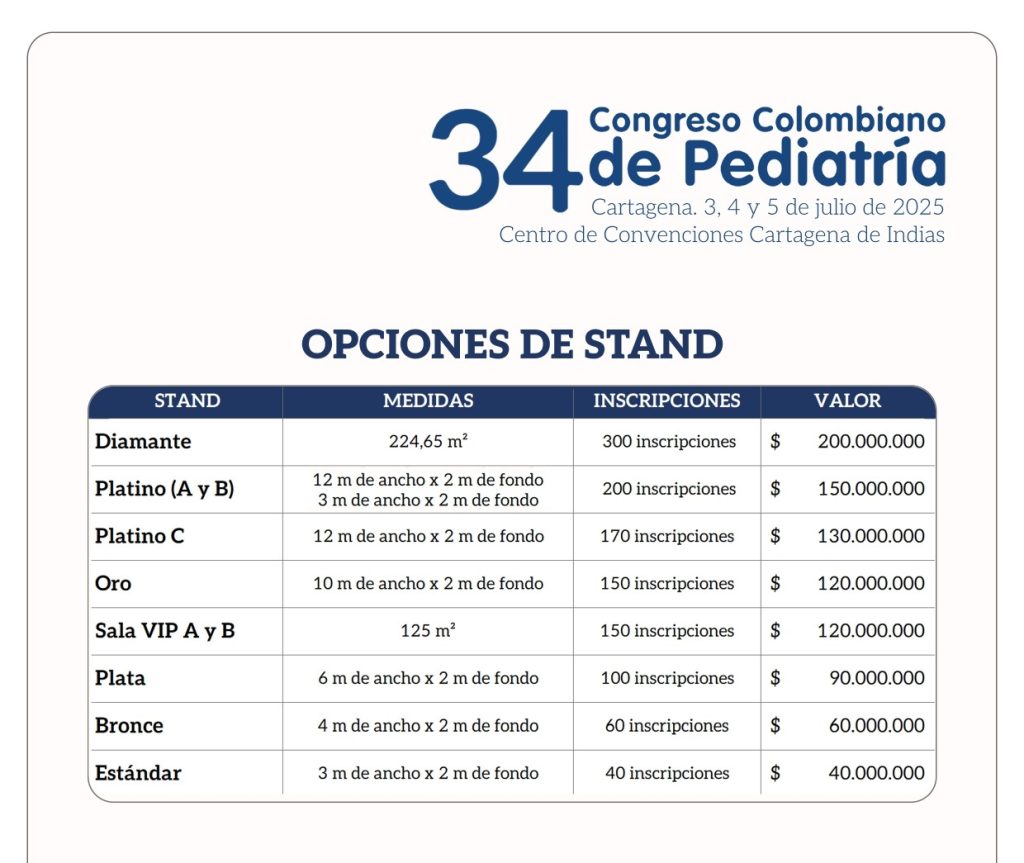

This model is reflected in the attached table, which shows the stands the SCP is currently negotiating with the industry for its Colombian Pediatric Congress, to take place next July. The table shows that every company that purchases space acquires a number of free registrations for pediatricians for the event: those paying $200 million COP for the largest stand can invite 300 doctors; those paying $40 million COP for one of the smallest can invite 40.

This also shows that the task of recruiting doctors for the congress is not—at least not for the most part—in the hands of the SCP, which organizes the event, but rather in the hands of ultra-processed food and pharmaceutical companies, who fund it. A look at the table containing the list of all stands available at the Colombian Congress of Pediatrics makes it clear that these industries have the potential to easily provide the 3,000 pediatricians that the SCP expects at the meeting.

In its response to VORÁGINE, the SCP admitted that it offers companies free registration for doctors when they purchase space: “This way (these companies) can contribute to the continuing medical education of the country’s health professionals.”

The problem is that this supposed contribution often exposes doctors to conflicts of interest.

Once a company purchases a stand at the SCP, the job of recruiting pediatricians to register for the event is usually left to medical sales representatives: employees of the industry’s marketing offices who hang around clinics, hospitals, and offices to pitch to doctors the products they want them to prescribe—such as infant formula—and thus increase sales.

A pediatric resident in Bogotá, who preferred to remain nameless, says that visiting doctors often approach students like her, who are doing their internships in a hospital, through the university hospitals’ chief residents. The chief residents agree to invite doctors to meetings outside the medical centers, where a doctor affiliated with the representative’s company will give a 15-minute talk on a topic of interest. The representative who made this space available uses it to promote his company’s products and offer incentives to the doctors, such as event tickets.

The student interviewed says that residents and pediatricians have a genuine interest in learning something from these talks, but, she adds, “[the talks] are also a way to obtain free registration fro a conference that can cost a million and a half pesos.” If you accept, the visitors don’t give you money; they just take care of the paperwork and then tell you: ‘I’ve already gotten you a ticket to the conference,’ ‘I’ve already got you a plane ticket,’ and they send you a photo of the ticket; ‘I’ve already got you a hotel,’ and they send you a photo of the reservation. For its upcoming Congress in Cartagena, the SCP is also offering companies the opportunity to organize ten symposia for attending pediatricians and physicians as part of the event, as another way of taking money in exchange for ensuring close contact with physicians. As an example, here is a table with the prices being used; companies are being charged $20 million COP to hold symposiums in the morning and $25 million COP to hold them during a luncheon.

This SCP approach violates the Breastfeeding Code and ignores international recommendations to prevent practices promoting infant formula to the detriment of breastfeeding. It does so while simultaneously highlighting among its achievements the fact that it helped promote the first Colombian Consensus on Breastfeeding and the Colombian Consensus on Complementary Feeding. This ambiguity plays out in a sensitive context for Colombia, where only 36 out of every 100 children are exclusively breastfed until six months, according to the most recent National Survey on Nutrition (2015). These figures are lower than those of Peru, Bolivia and Guatemala.

The same survey made clear the key role that pediatricians and healthcare professionals play in mothers’ decisions, as 79% of those who received the recommendation to use formula instead of breast milk were advised by a healthcare professional. This result was corroborated by the most recent monitoring of application of the Code in Colombia, carried out in 2021 by Educar Consumidores and the International Baby Food Action Network (IBFAN, for its English acronym), an organization that has questioned SCP practices.

Silence in the Labeling Law… and Rebellion of Bogotá’s Regional Government

“We know we can’t rely on the SCP for any of our actions,” says Rubén Orjuela, a nutritionist who heads Educar Consumidores and IBFAN Colombia, organizations that have been warning for decades about the dangers to children’s health caused by excessive consumption of ultra-processed food products and the marketing tactics employed to promote them.

Adding to this discredit is Red Papaz, an NGO that defends the rights of children and adolescents and is a leader in discussions about ultra-processed foods and sugary drinks. Red Papaz was one of the main proponents of the front-of-package labeling law, which required the industry to place black, octagonal labels on products containing excess sodium, saturated fat, trans fat, added sugars, and artificial sweeteners. Its director, Carolina Piñeros, recalls that a decade ago she suffered “a tremendous shock” when the SCP invited her to a conference where ultra-processed food industries were promoting products, including infant formula. “I recognize the importance of the SCP in certain areas,” she adds, “but in the case of infant formula, the national management, headed by Gloria Zuccardi has a very serious conflict of interest. They use a double standard: on the one hand, health, well-being, and child-rearing; on the other, business.”

Criticism has also grown among doctors; the Bogotá Regional Office of the SCP in the country’s capital has established itself as the only dissident.

The 24 regional branches of the organization each have the authority to raise funds to hold local academic events. In 2018, the pediatricians on the board of the Bogotá Regional Office voted to veto any contributions from companies that manufacture infant formula, explains María Lucía Mesa, who was president of that Regional Office until 2024. They created a fund to which other industries, such as the pharmaceutical and vaccine industries, can donate money, but, unlike the national branch office, the regional branch does not sell stands to these industries and, therefore, does not allow them to promote products to pediatricians. The branch does recognize them at events, mentioning which companies in that sector helped make it possible, although without mentioning specific product brands. “The industry’s influence on the decisions of parents and pediatricians has always been a challenge for us,” says Mesa. “It was inconsistent to allow them to sponsor our events. We had many awkward encounters with colleagues and people in the industry because pediatric societies often rely on this type of sponsorship.”

The Bogotá Regional Office—which accounts for nearly half of the 5,000 pediatricians affiliated with the SCP—is the only SCP branch to have banned the infant formula industry so far. A simple Google search will show you, for example, that Mead Johnson is a client of the Valle del Cauca regional branch; you can also watch a presenter at a Cauca regional event thanking Nestlé, Sanulac, and Mead Johnson’s infant formula brands for their sponsorship.

It was the Bogotá Regional Office, in fact, that fully supported the front-of-package labeling project for ultra-processed foods six years ago, alongside organizations such as Educar Consumidores and Red Papaz. The institutional letter that the pediatricians’ union sent to Congress to support the project was from this branch, not the national one.

The Bogotá Regional Office’s stance was finally dismissed following a power struggle, which it lost to the group of executives who support the financing model led by Zuccardi. As a result of this struggle, the Bogotá branch lost influence inside the SCP and, for almost eight years, has had no representation on the board of directors, which is elected by the pediatricians’ regional representatives from all the branches.

Illustrated infographic: The Winding Path of Colombia’s Front-of-package Labeling Law Project

“We don’t demonize collaboration with industry”

On July 3, 2019, the then president of the SCP, pediatrician Marcela Fama, presented a campaign at the SCP’s National Assembly to promote several messages of the organization’s commitment to child welfare. Among these was one in defense of breastfeeding. Minutes later, according to the meeting minutes, she announced that “we are working with Nestlé Colombia to prepare residents for their upcoming work as pediatricians.” They would do this, she said, through Jpedia, an educational platform that the multinational company set up years ago for pediatric residents.

By that time, the SCP was already receiving money from Nestlé for promoting the educational platform in its magazine sent out to residents (a publication for which they have also received money for infant formula advertising). This is an example of a JPedia advertisement from an early 2019 issue:

Pediatrician María Isabel Uscher of the Bogotá Regional Office took the floor to describe the alliance with Nestlé as an incongruity while the breastfeeding campaign was being announced. She also questioned the fact that the magazine Crianza y Salud (the same SCP publication that years ago had been used to advertise Pony Malta, Chocolisto, and Alpinito) would then be reaching pediatricians and parents with “ads for Alpina and Nestlé breast milk substitutes.” Here is an example from that year:

—A stand must be taken now! “It’s an ethical issue,” Uscher told the SCP executives in front of the other attendees.

As in the 2004 debate about Pony Malta, ethics remained at the heart of some pediatricians’ complaints about the organization’s commercial agreements. Zuccardi responded to Uscher:

—That would be ideal, but we must consider whether it’s possible to work without support from industry.

The truth is, Zuccardi has never worked any other way.

Two years later, on July 6, 2021, when the current national SCP president, pediatrician Mauricio Guerrero from Cartagena, was elected to that position in an online meeting, Dr. Uscher again protested the continued presence of the formula industry at congresses and, in the meeting chat, she asked the new president about his relationship with that industry and how he would handle conflicts of interest. But, according to the minutes, she got no answer.

Today, Guerrero has already served two terms as president of the SCP, working closely with Zuccardi. VORÁGINE approached them, as heads of the organization, for this report and they requested written questions to which they would respond. They returned a document that Guerrero signed and had notarized as a sworn statement.

His answers revolve around two arguments. Firstly, that “in recent years, contributions from the food industry have represented 7.5% of our total revenue, which shows that it is neither a predominant nor a determining source of funding.”

The statement assured that funding comes from diverse sources, such as academic events and publications. However, the sale of stands at events and advertising for publications is restricted, according to a message from the SCP itself, and limited to only the pharmaceutical and food and beverage industries. Although VORÁGINE enquired as to the main sources of the SCP’s income, we received no answer, except for point outing that, if the SCP wanted, they could do without the money they receive from the ultra-processed food company. “However,” they added, we don’t demonize collaboration from the industry.”

Their second argument: “We do not believe that our work or our interaction with the pharmaceutical and consumer industries generates conflicts of interest that affect our decision-making autonomy.” However, when asked for evidence of their positions on bills that have sought to regulate the ultra-processed food industry (which they call “consumer” bills), such as front-of-pack labeling and healthy taxes (now law), and the Gloria Ochoa bill (which sought to promote breastfeeding, and failed), the SCP responded evasively, saying it has worked with entities such as the Andi, the Ministry of Health and the Health Secretariats on matters of child nutrition. They did not, however, refer to the legislation projects.

SCP management, led by Executive Director Gloria Zuccardi, will continue working with the industry, despite the internal and external criticism they continue to receive. Zuccardi’s work has been so fluid, in fact, that, while remaining in her position at the SCP, she and two former SCP presidents created a company a few years ago to do business with pharmaceutical and ultra-processed food companies. An enterprise that, far from operating outside the SCP, given the obvious conflict of interest this would represent, has enjoyed the unrestricted support of the organization’s other board members, as we will show in the second installment of this investigation.

* This investigation was funded, in part, by Vital Strategies. The content is editorially independent and is intended to shine a light on illegal or unethical practices in the food and beverage industry and on the fact that it is the most vulnerable populations who disproportionately bear the brunt of the health crisis caused by the consumption of unhealthy food and beverages. Unless otherwise noted, all statements published in this story, including those regarding specific legislation, reflect the views of the particular organizations, and not of Vital Strategies.

** Editor’s note: On May 4, 2025, one week after this investigation was published, the attorney representing the Colombian Pediatric Society and its executive director, Gloria Zuccardi, sent a request for clarification and correction regarding several points in this article. VORÁGINE declined to correct any of the statements made and stands by the findings of the investigation. However, it agreed to include three additional facts requested by the attorney, so that readers would have greater context about what happened, without implying that what is presented here is no longer supported: 1) We include, as background to the Pony Malta case, that in 2003 the Bogotá Regional branch of the SCP had signed a commercial agreement with Bavaria to promote Pony Malta. The proposal presented by executive director Gloria Zuccardi to an SCP board meeting in 2004 was to extend that agreement to the entire SCP, beyond the Bogotá Regional branch. 2) We expressly stated that the SCP does not currently endorse any products from the ultra-processed food industry. 3) We included, as additional context, that the SCP helped promote, along with other scientific societies, the first Colombian Consensus on Breastfeeding and the Colombian Consensus on Complementary Feeding.

If you have more information on this or other topics please write to carloshernandezoso@gmail.com